Lucretius

—

LUCRETIUS

[ Titus Lucretius Carus ]

—

(~94aC – ~50aC)

—

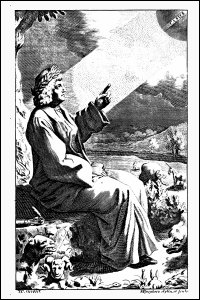

Classic Roman poet, naturalist and philosopher; follower of Greek Epicurean materialist (atomist), empiricist, rationalist and hedonist philosophic school.

—

His poem «DE RERUM NATURA» [On the Nature of Things], rediscovered at the beginning of century XV after a long oblivion period, opened to Western thinkers quite a new regard for the physical and spiritual world and a most challenging perspective on life, though becoming an underlying seed of European Modernity.

—

PORTRAITS: |

||

—

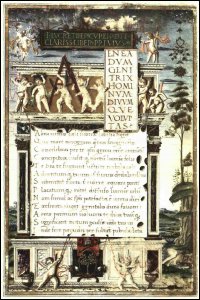

«DE RERUM NATURA»

—

In January 1417, a surviving copy of Lucretius’ Latin poem «DE RERUM NATURA» [On the Nature of Things] has been found and recovered by the Italian humanist Poggio Bracciolini [Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini] (1380-1459) in the library of a south German monastery.

—

Recognizing the immense value of a text that had been lost and forgotten for almost 1500 years, Poggio had it promptly copied and sent to friends in Florence who made and spread several new copies.

—

Lucretius’ poem, then and mainly after its first printing in 1473, in Brescia, Lombardy (Italy), in its original Latin text and/or in several translations into modern languages, regained a new life, continuing to shine till today.—

—

![]() —

—

—

Reading of «DE RERUM NATURA» in Latin original version (AudioAZ)

| https://audioaz.com/book/de-rerum-natura-by-titus-lucretius-carus |

—

Reading of «DE RERUM NATURA» in English translated version (AudioAZ)

| https://audioaz.com/book/nature-of-things-munro-by-lucretius |

—

![]()

—

—

ABOUT CLASSICAL (GREEK/ROMAN) FREEDOM OF THOUGHT

—

(some few notes from John B. Bury’s HISTORY OF FREEDOM OF THOUGHT)

—

—

IT is a common saying that thought is free. A man can never be hindered from thinking whatever he chooses so long as he conceals what he thinks. […] But this natural liberty of private thinking is of little value. It is unsatisfactory and even painful to the thinker himself, if he is not permitted to communicate his thoughts to others, and it is obviously of no value to his neighbours.

[…]

At present, in the most civilized countries, freedom of speech is taken as a matter of course and seems a perfectly simple thing. We are so accustomed to it that we look on it as a natural right. But this right has been acquired only in quite recent times, and the way to its attainment has lain through lakes of blood. It has taken centuries to persuade the most enlightened peoples that liberty to publish one’s opinions and to discuss all questions is a good and not a bad thing. Human societies […] have been generally opposed to freedom of thought, or, in other words, to new ideas, and it is easy to see why.

[…]

The average brain is naturally lazy and tends to take the line of least resistance. The mental world of the ordinary man consists of beliefs which he has accepted without questioning and to which he is firmly attached; he is instinctively hostile to anything which would upset the established order of this familiar world. A new idea, inconsistent with some of the beliefs which he holds, means the necessity of rearranging his mind; and this process is laborious, requiring a painful expenditure of brain-energy.

[…]

In the Middle Ages a large field was covered by beliefs which authority claimed to impose as true, and reason was warned off the ground. But reason cannot recognize arbitrary prohibitions or barriers, without being untrue to herself. The universe of experience is her province, and as its parts are all linked together and interdependent, it is impossible for her to recognize any territory on which she may not tread, or to surrender any of her rights to an authority whose credentials she has not examined and approved.

The uncompromising assertion by reason of her absolute rights throughout the whole domain of thought is termed rationalism, and the slight stigma which is still attached to the word reflects the bitterness of the struggle between reason and the forces arrayed against her. The term is limited to the field of theology, because it was in that field that the self-assertion of reason was most violently and pertinaciously opposed. In the same way free thought, the refusal of thought to be controlled by any authority but its own, has a definitely theological reference.

[John B. Bury, 1913]

—

—

—

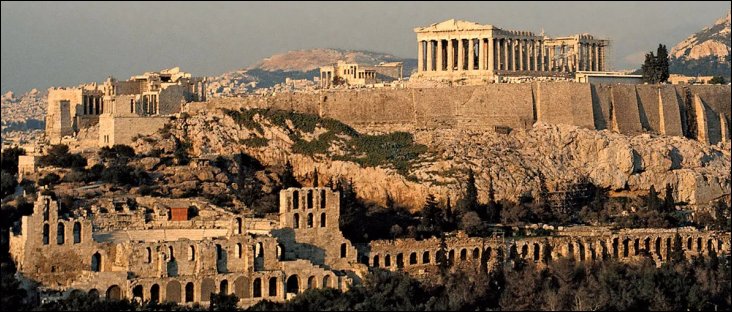

When we are asked to specify the debt which civilization owes to the Greeks, their achievements in literature and art naturally occur to us first of all. But a truer answer may be that our deepest gratitude is due to them as the originators of liberty of thought and discussion. For this freedom of spirit was not only the condition of their speculations in philosophy, their progress in science, their experiments in political institutions; it was also a condition of their literary and artistic excellence. […] But apart from what they actually accomplished, even if they had not achieved the wonderful things they did in most of the realms of human activity, their assertion of the principle of liberty would place them in the highest rank among the benefactors of the race; for it was one of the greatest steps in human progress.

[…]

The outcome of the large freedom permitted at Athens was a series of philosophies which had a common source in the conversations of Socrates. Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, the Epicureans, the Sceptics – it may be maintained that the efforts of thought represented by these names have had a deeper influence on the progress of man than any other continuous intellectual movement, at least until the rise of modern science in a new epoch of liberty.

The doctrines of the Epicureans, Stoics, and Sceptics all aimed at securing peace and guidance for the individual soul. They were widely propagated throughout the Greek world from the third century B.C., and we may say that from this time onward most well-educated Greeks were more or less rationalists. The teaching of Epicurus had a distinct anti-religious tendency. He considered fear to be the fundamental motive of religion, and to free men’s minds from this fear was a principal object of his teaching. He was a materialist, explaining the world by the atomic theory of Democritus and denying any divine government of the universe. He did indeed hold the existence of gods, but, so far as men are concerned, his gods are as if they were not – living in some remote abode and enjoying a “sacred and everlasting calm”. They just served as an example of the realization of the ideal Epicurean life.

[…]

There was something in this philosophy which had the power to inspire a poet of singular genius to expound it in verse. The Roman Lucretius (first century B.C.) regarded Epicurus as the great deliverer of the human race and determined to proclaim the glad tidings of his philosophy in a poem On the Nature of the World [De Rerum Natura]. With all the fervour of a religious enthusiast he denounces religion, sounding every note of defiance, loathing, and contempt, and branding in burning words the crimes to which it had urged man on. He rides forth as a leader of the hosts of atheism against the walls of heaven. He explains the scientific arguments as if they were the radiant revelation of a new world; and the rapture of his enthusiasm is a strange accompaniment of a doctrine which aimed at perfect calm. Although the Greek thinkers had done all the work and the Latin poem is a hymn of triumph over prostrate deities, yet in the literature of free thought it must always hold an eminent place by the sincerity of its audacious, defiant spirit. In the history of rationalism its interest would be greater if it had exploded in the midst of an orthodox community. But the educated Romans in the days of Lucretius were sceptical in religious matters, some of them were Epicureans, and we may suspect that not many of those who read it were shocked or influenced by the audacities of the champion of irreligion.

The Stoic philosophy made notable contributions to the cause of liberty and could hardly have flourished in an atmosphere where discussion was not free. It asserted the rights of individuals against public authority. […] The Stoics discovered it in the law of nature, prior and superior to all the customs and written laws of peoples, and this doctrine, spreading outside Stoic circles, caught hold of the Roman world and affected Roman legislation.

[John B. Bury, 1913]

—

—

There [in Classic Antiquity] was however a school of philosophical speculation, which might have led to the foundation of a theory of Progress, if the historical outlook of the Greeks had been larger and if their temper had been different. The Atomic theory of Democritus seems to us now, in many ways, the most wonderful achievement of Greek thought, but it had a small range of influence in Greece, and would have had less if it had not convinced the brilliant mind of Epicurus. The Epicureans developed it, and it may be that the views which they put forward as to the history of the human race are mainly their own superstructure. These philosophers rejected entirely the doctrine of a Golden Age and a subsequent degeneration, which was manifestly incompatible with their theory that the world was mechanically formed from atoms without the intervention of a Deity. For them, the earliest condition of men resembled that of the beasts, and from this primitive and miserable condition they laboriously reached the existing state of civilisation, not by external guidance or as a consequence of some initial design, but simply by the exercise of human intelligence throughout a long period.

The gradual amelioration of their existence was marked by the discovery of fire and the use of metals, the invention of language, the invention of weaving, the growth of arts and industries, navigation, the development of family life, the establishment of social order by means of kings, magistrates, laws, the foundation of cities. The last great step in the amelioration of life, according to Lucretius, was the illuminating philosophy of Epicurus, who dispelled the fear of invisible powers and guided man from intellectual darkness to light.

But Lucretius and the school to which he belonged did not look forward to a steady and continuous process of further amelioration in the future.

[John B. Bury, 1920]

—

— — …

— — Usus et impigrae simul experientia mentis

— — Paulatim docuit pedetemtim progredientis.

— — Sic unum quicquid paulatim protrahit aetas

— — In medium ratioque in luminis erigit oras.

— — Namque alid ex alio clarescere et ordine debet

— — Artibus, ad summum donee uenere cacumen.

— — …[… as men progressed gradually step by step, all achievements were taught by practice and the experiments of the active mind. So, by degrees, time brings up before us every single thing, and reason lifts it into the precincts of light. For they saw one thing after another grow clear in their minds, until they attained the highest pinnacle of the arts.]

[Lucretius – 1st century bC]

—

![]()

—

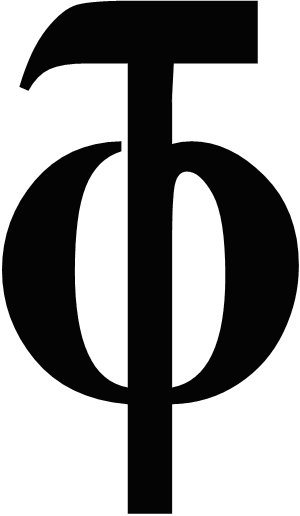

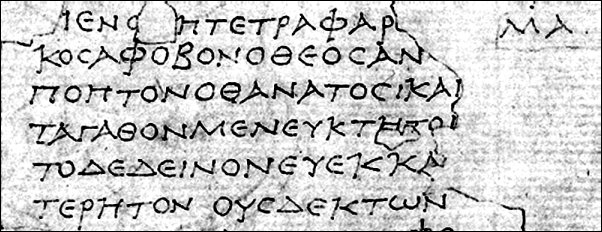

Tetrapharmakos (τετραφάρμακος)

[Epicurian’s four part remedy]

—

The Tetrapharmakos (τετραφάρμακος) [four-part remedy] summarises the first four of the forty Epicurean principal recommendations given by Diogenes Laërtius in his Life of Epicurus – the principal doctrines, «Kuriai Doxai» (Κύριαι Δόξαι), of Epicureanism –, a recipe for leading the happiest possible life avoiding anxiety or existential dread:

- Don’t fear god (Ἄφοβον ὁ θεός)

- Don’t worry about death (ἀνύποπτον ὁ θάνατος)

- What is good is easy to get (καì τἀγαθòν μεν εὔκτητον)

- What is terrible is easy to endure (τò δε δεινòν εὐεκκαρτέρητον)

—

| —

|

|

![]()

—

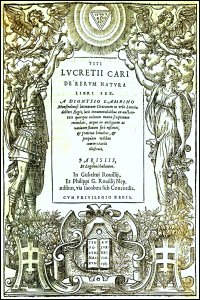

RENAISSANCE AND MODERN REDISCOVERY OF «DE RERUM NATURA»

—

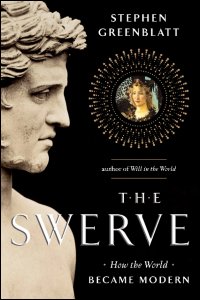

The story of the rediscovery of Lucretius’ «DE RERUM NATURA», and its sequent decisive repercussions on European social/cultural secularisation (laicisation) and the development of modern scientific thought, became the subject of Stephen Greenblatt’s remarkable book entitled THE SWERVE: HOW THE WORLD BECAME MODERN (2011).

—

Stephen Greenblatt (1943-) |

cover of 1st edition (2011) |

frontpage of 1st edition (2011) |

—

Stephen Greenblatt –

THE POEM THAT DRAGGED US OUT OF THE DARK AGES

—

—

‘THE SWERVE’: WHEN AN ANCIENT TEXT REACHES OUT & TOUCHES US

—

—

Stephen Greenblatt –

LUCRETIUS AND THE TOLERATION OF INTOLERABLE IDEAS

—

—

—

—

Nothing can dwindle to nothing, as Nature restores one thing from the stuff of another, nor does she allow a birth, without a corresponding death. [translated]

—

Lucretius [Titus Lucretius Carus] (~99BC-~55BC)

—

—