J.B.Bury’s works – 1891

—

ANIMA NATURALITER PAGANA*

A QUEST OF THE IMAGINATION

[* soul naturally pagan]

—

by John B. Bury

—

Published in: THE FORTNIGHTLY REVIEW, N.S. XLIX, 1891, (pp.102-112)

—

| 2 copies available: | |

|

|

|

|

—

—

… Bury’s “restless and fertile mind”, to quote Arnaldo Momigliano’s telling phrase, led him to ponder another thorny question that besets the philosophically inclined historian: what is the nature of historical cognition? Is it inevitably subjective and, if so, in what sense can history be considered a science? Bury’s earliest reflections on these questions can be found in a short article, “Anima Naturaliter Pagana”, published in 1891. In this essay he argued that it is impossible to recover the pagan past, whatever one’s resources of knowledge and empathy. The modes of thought and feeling in the historian’s environment cannot be discarded, and these present an insuperable obstacle to the apprehension of alien cultures“. … [p.904]Doris S. Goldstein (1977)

—

![]()

—

—

It is a commonplace with critics that the creative faculty in literature is well-nigh exhausted, and that all works produced nowadays are merely variations on old motives and modifications of old ideas. … Yet it might be plausibly argued that to understand what is really old requires a powerful imagination as to invent what is really new. Perhaps, indeed, both tasks are impossible, if “new” in the one case and “understand” in the other be taken in the strictest sense. … It is just because so few have more than a merely speculative interest in the problem of understanding the mind and the art of the ancient Greeks, that the difficulties involved in that problem have seldom been sufficiently realised. [p.102]

[John Bagnell Bury – 1891]

—

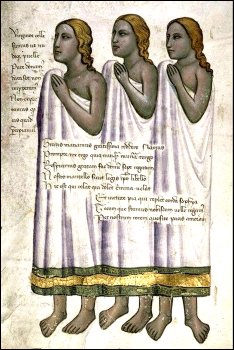

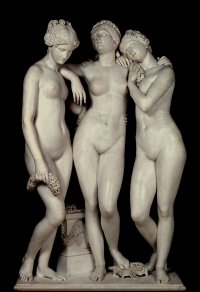

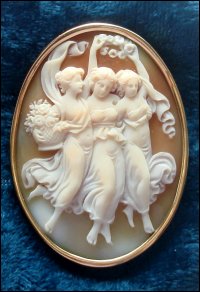

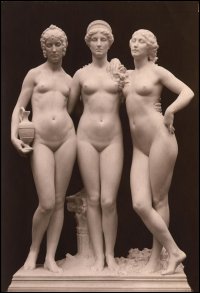

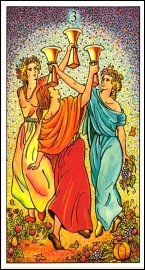

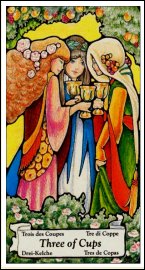

Χάριτες [Charites] Greek and Hellenistic times

Ἀγλαΐα [Aglaea or Aglaïa] • Εὐφροσύνη [Euphrosyne] • Θαλία [Thalia]

Gratiae [Graces] Roman times

—

—

… it may be interesting to inquire, as a mere matter of speculation, whether such a quest is doomed to fail or destined to succeed; and the problem clearly touches on questions which have some importance for all students of literature, and especially for classical scholars. We hear a good deal, now and then, about the necessity of placing oneself at the ancient point of view, or of thinking oneself into the Greek mind. But how far it this psychologically possible? In some cases it is easy enough to recognise that the Greeks looked on such and such a matter in such and such a way, whereas modern civilisation regards the same thing otherwise. But this is by no means equivalent to the realisation of the Hellenic temper. … [and] a certain approximation at least to this ideal must be recognised as desirable by every student of Greek art and literature. … [p.103]

[John Bagnell Bury – 1891]

—

—

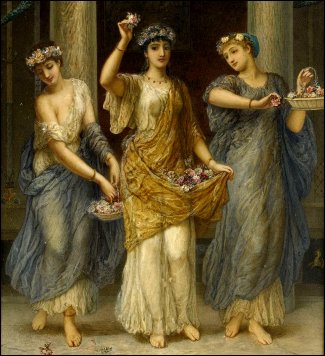

… Of characteristics of Greek art which render its appreciation in any real sense by the modern mind possible only after a careful training of the imagination, two are specially obvious. These are temperance and cheerfulness (σωϕροσύνη and ϵὐϕροσύνη). It is true that all art exacts a certain measure of self-restraint, but much of the best modern art expresses passions of a soul which does not care to control itself. Temperance was the note of the Greek spirit; whereas the modern spirit is naturally extravagant, and if gravitation to “the Infinite” is kept within due limits, that repression is due to our familiarity with classical models. … [p.104]

…

Now the modern man may train himself to take pleasure in the temperance of Greek art, but he must remember that this vital difference between the Greek and the modern temper has wide effects in language and in small details, which with all watchfulness and subtlety he can hardly hope to follow. He will find it still more difficult to understand and appreciate another mark of the Greek mind and the art which it informed. The spirit of self-restraint was accompanied by cheerfulness. The Greeks were content with limits, and cheerful within them; … they were not “sick or sorry”. … [p.105][John Bagnell Bury – 1891]

—

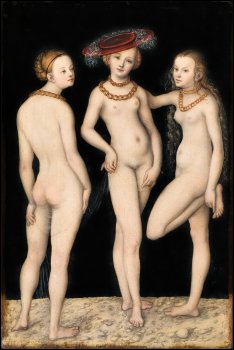

Three Graces – Medieval, Renaissance…

Three Graces – Classicism, Mannerism, Baroque…

—

—

… We too have the cheerful, we have literature animated by various forms of cheerfulness. But this only increases out difficult in realising the Greek mood; for we have to keep it uninfected by the somewhat grotesque cheerfulness of Rabelais on the one hand, and by what Bacon calls a “devout cheerfulness on the other. The humanist who revived the memories of antiquity, and awakened the world and conducted it out of darkness into a new light, did not succeed in reinstating the Greek Grace. … [p.105][John Bagnell Bury – 1891]

—

—

… When we reflect, that, not only we ourselves have been brought up and live in an atmosphere wholly different from the Greek and inhabited by a music that is acquainted with emotions which to the Greeks were utterly unknown, but our forefathers, who made us what we are, have for centuries past been thinking things which never entered the thought of Plato, and feeling things of which Sophocles and Pericles never dreamed, we can apprehend the magnitude of the task awaiting him who would really cross the ages in the little bark of the mind. We no longer, indeed, look up to the ideals of our ancestors … But these ideals brought forth their fruits, and they are psychologically affecting us still. They conditioned the growth of forces which overthrew them, and they formed minds which struck into new paths. … [p.106][John Bagnell Bury – 1891]

—

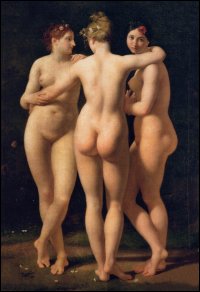

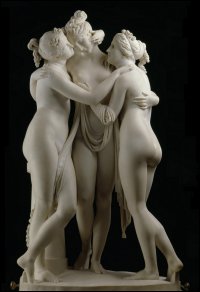

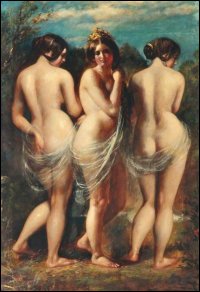

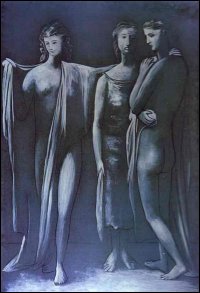

Three Graces – Neo-Classicism, Romanticism…

Three Graces – Pre-Raphaelits…

—

—

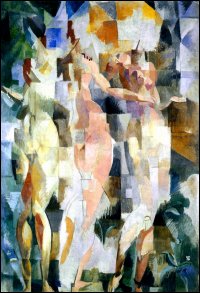

But the difficulties are by no means exhausted. There is a modern art amongst us, which deals in various ways with Hellenic subjects. Out of the stories of Greek myth modern poets and painters have constructed new “classical” worlds, not, however, really classical, but transmuted in their crucibles and tempered into romanticism. In spirit, if not in letter, the legends told and painted by the new artists are as unlike the old, as the Arcadia of the Renaissance is unlike the Arcadia of geography. But it is from the new vessels that we drink in our early childhood. … [p.107][John Bagnell Bury – 1891]

—

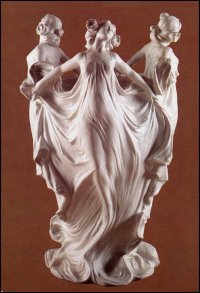

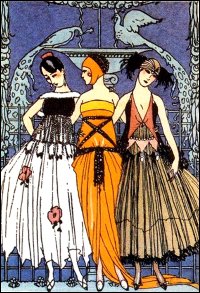

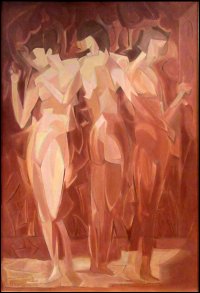

Three Graces – Art-Nouveau, Art-Deco, Expressionism, Modernism …

![]()

—

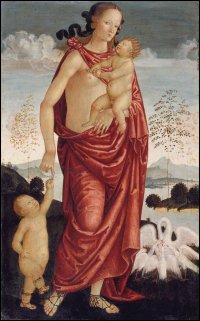

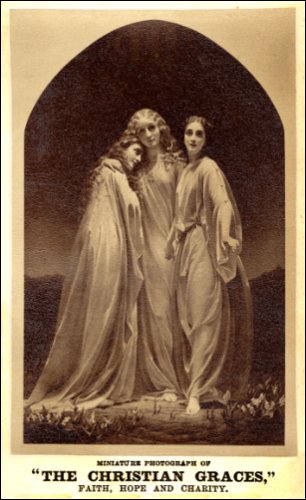

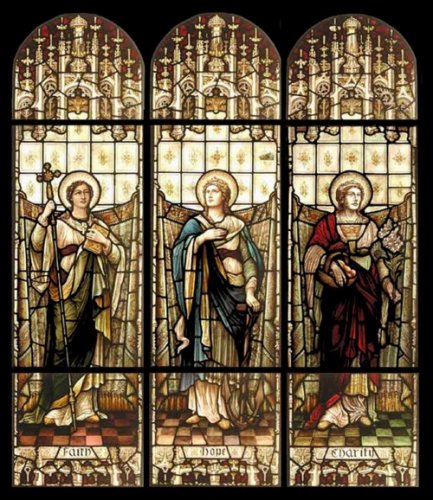

Christian Graces [Theological virtues: Faith, Hope, Charity]

|

|

—

![]()

—

Three Graces – Advertising

![]() —

—

Three Graces – Tarot [Three of Cups]

|

|

|

|

—

—

—

—

This idea [Progress] means that civilisation has moved, is moving, and will move in a desirable direction. But in order to judge that we are moving in a desirable direction we should have to know precisely what the destination is. To the minds of most people the desirable outcome of human development would be a condition of society in which all the inhabitants of the planet would enjoy a perfectly happy existence. But it is impossible to be sure that civilisation is moving in the right direction to realise this aim.

—

John B. Bury (1861-1927)

—

—

![]()